THE FATHER OF TEXAS BOTANY

A bold & independent explorer

You may not have heard of Ferdinand Lindheimer, but his name is planted all over Texas.

Lindheimer’s Muhly, Lindheimer’s daisy, Lindheimer’s indigo, Lindheimer’s beargrass, Lindenheimer’s bee blossom, the prickly pear cactus (opuntia Lindheimeri) … those are only a fraction of the native plants of Texas that bear this extraordinary Texas explorer’s name. There are so many plants he collected and identified he is widely known as the “Father of Texas Botany.”

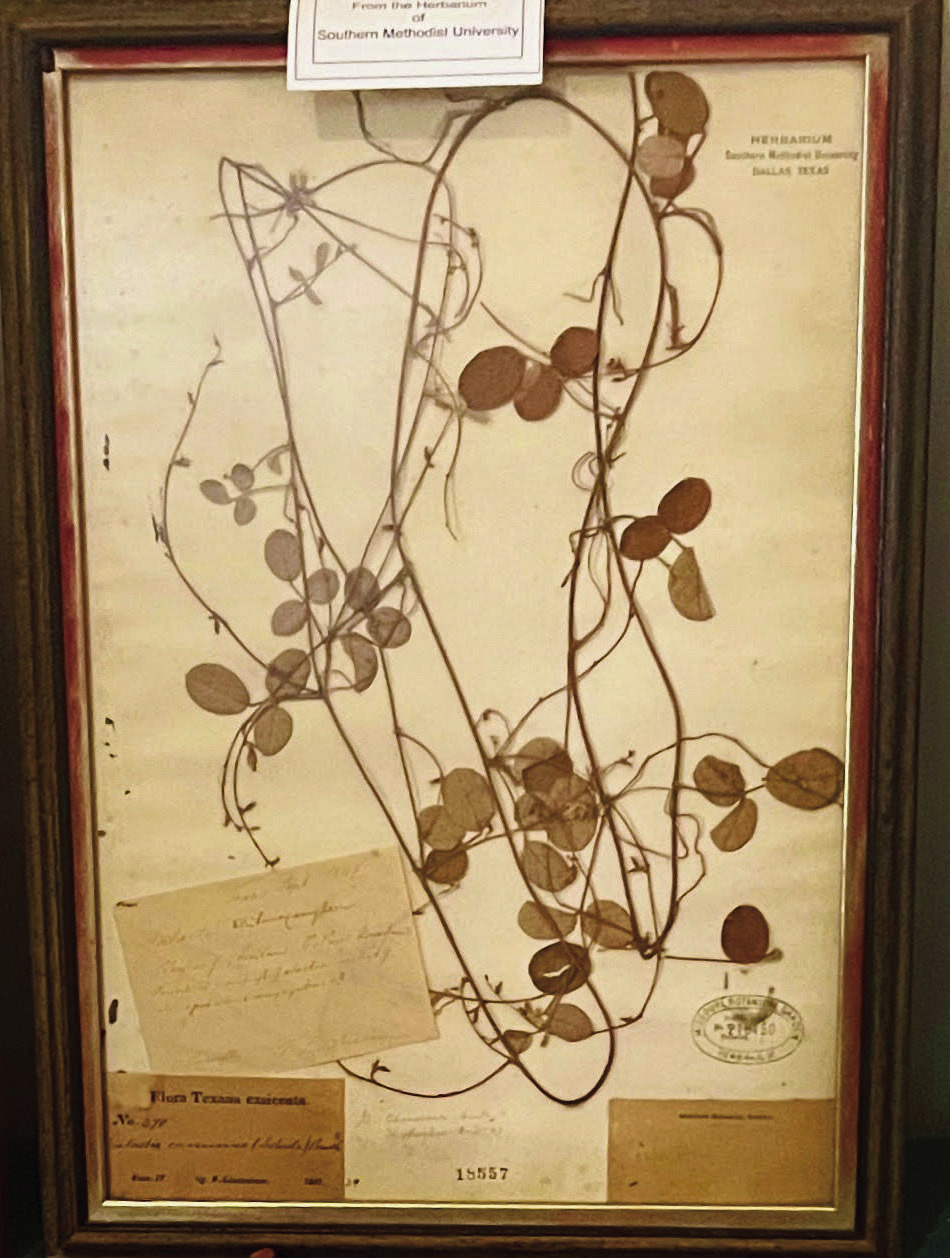

Between 1836 and 1879, Lindheimer collected thousands of plants from all over Texas, particularly between the Gulf Coast and the Hill Country. Today, more than 30 different plants bear his name. In all, more than 370 scientific names of plants are based, at least in part, on Lindheimer collections.

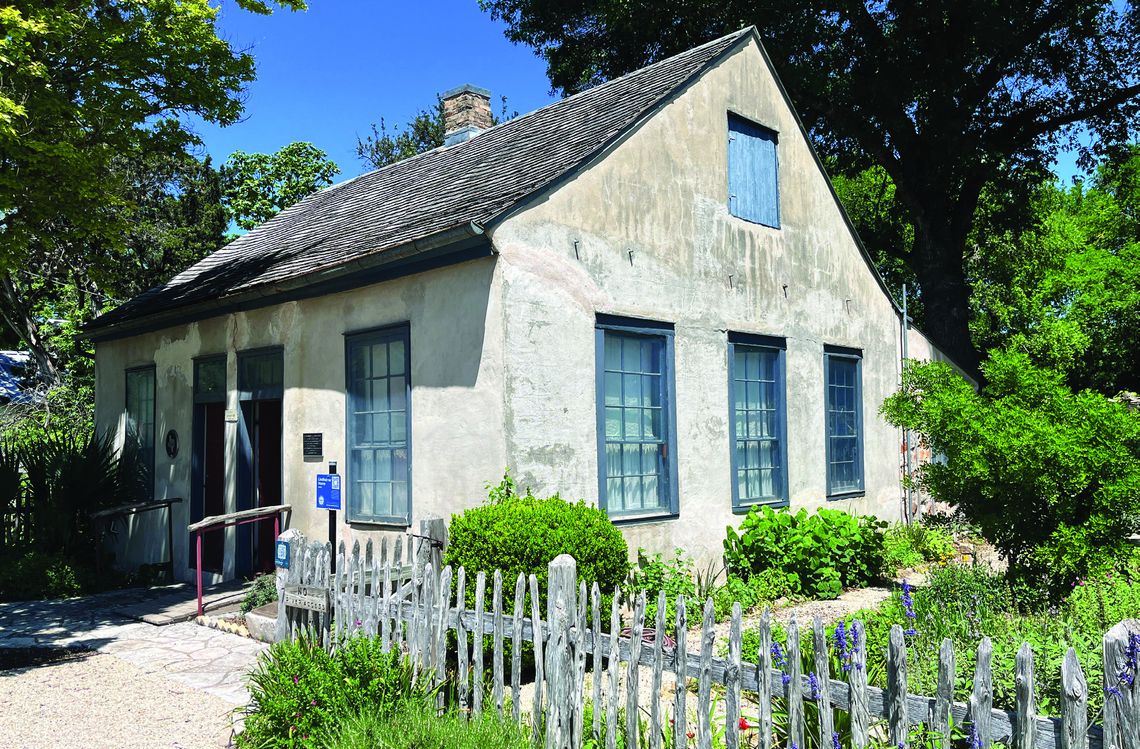

LINDHEIMER HOME COURTESY NEW BRAUNFELS CONSERVATION SOCIETY

Unless you’re a naturalist, the “Father of Texas Botany” might conjure up an image of a mild-mannered little fellow who sits around peering at plants with a magnifying glass. The real story might surprise you. Ferdinand Lindheimer was a bold, independent spirit – a bold justice seeker with an unquenchable thirst for knowledge and a passion to share it.

Born in Germany in 1801, Lindheimer was raised in a wealthy family and an intellectual environment. The great German philosopher and writer Goethe was a cousin. He studied philosophy and literature and began a career teaching at a university. Who could have guessed that privileged young man would be roaming the wild Texas prairie a few decades later?

In 1833, when a repressive German government exiled several of his university colleagues, Lindheimer embarked on a journey to America, where new freedoms beckoned. German settlements were already popping up in the U.S. and Mexico by that time. He stopped for a few months with old friends in Illinois, where he worked on a farm, and not too long after headed for a more adventurous journey to Mexico. He embarked on a Mississippi riverboat to New Orleans and caught a schooner to Vera Cruz, Mexico, where another German settlement welcomed him. Never afraid to get his hands in the soil, Lindheimer worked on a banana plantation there for a year or two.

A natural-born freedom fighter, Lindheimer was stirred by news of the Texas Revolution. When Texas rebels sent out a call for volunteers, he boarded a ship to join the fray. The trip was delayed when the vessel shipwrecked off the Alabama coast. But Lindheimer pressed on to Texas to join Sam Houston’s army. He finally arrived at San Jacinto to join Sam Houston’s army of the Republic of Texas.

His timing was perfect. He arrived the day after the Battle of San Jacinto in time to see Santa Anna’s surrender. He joined the new republic’s army anyway and served for nearly two years. In his spare time, he studied the trees and plants in his new home.

The wild landscape captivated Lindheimer. Botany – the scientific study of plants – was a prominent field of research in those days, and Lindheimer’s intellectual bent led him to study what he found. Collecting also turned into a means of making his living. In 1839, Lindheimer took a collection of his plants to George Englemann, an old friend from Frankfurt practicing medicine in St. Louis and studying botany on the side. The specimens excited Englemann enough to contact Asa Gray, a renowned botanist at Harvard University, who literally wrote the book on North American plants.

Legend has it that Native American Chief Santana was so taken with one of Lindheimer’s blue-eyed blonde little boys that he offered to trade a mule and a young Comanche girl for the toddler.

MASTER GARDENER ANDY GATHANY WITH PURPLE PHLOX IN THE LINDHEIMER HOME GARDEN - CREDIT SANDRA GATHANY

Englemann and Gray offered to take Lindheimer’s collections

on

“subscription”

– he received a few cents for each dried specimen he sent them. Gradually, his plants found their way to botanists around the world.

“Basically, he was doing the fieldwork for them,” said Phillip Schulze, site director of the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center in Austin, where Lindheimer’s name is well known.

“ For instance, he would collect 20 duplicate herb specimens and ship the material to St. Louis. From there, they would be distributed around the world to various scientific collections of preserved plant specimens called herbaria. Those people were also paying a fee per specimen, and that money supported him. The reason he has so many things named after him is that he was the first one to make those collections.”

“He was unique,” Schulze said. “He was here in Texas before the main body of the German immigration arrived. He was in communication with Native Americans… he was an odd person, when you think of it – a lone gringo out on the frontier looking at plants.”

One contemporary described Lindheimer as a blue-eyed man with a bushy black beard, roaming central and coastal Texas in a two-wheeled cart with a horse, a rifle, two hunting dogs, and enough paper to pack and preserve his plants.

“He would collect 20 duplicate herb specimens and ship the material to St. Louis. From there, they would be distributed around the world to various scientific collections of preserved plant specimens called herbaria.”

— Phillip Schulze Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center Native Americans came to know him as the discoverer of healing herbs and left him in peace.

LINDHEIMER SPECIMEN SAMPLE IN THE NEW BRAUNFELS CONSERVATION SOCIETY’S LINDENHEIMER HOME - PHOTO BY SUSAN YERKES

NEW BRAUNFELS MASTER GARDENER AND GUIDE JERRY FINKE WITH NEWSPAPER MEMORABILIA IN THE LINDHEIMER HOME CREDIT SUSAN YERKES

In 1844, he heard Prince Carl Solms- Braunfels, a German colonist, was bringing a group of settlers to Texas. He met the ship at Indianola in Matagorda Bay and accompanied the settlers to their new home, serving as a guide and unpaid guard for the prince, who granted him a plot of land in the town he formed, New Braunfels.

Once there, he settled down, married, and raised children. He had become friends with Chief Santana of the Comanche tribe, who often visited him. Legend has it that Chief Santana was so taken with one of Lindheimer’s blue-eyed blonde little boys that he offered to trade a mule and a young Comanche girl for the toddler. Lindheimer politely declined.

He started a free primary school and then served as superintendent of the first public school in the area. He also started a German-

language newspaper, the Neu Braunsfelser

Zeitung. He was known as a stubborn man with strong opinions, and those opinions sometimes caused controversy. One of his editorials riled enough people that some citizens seized his printing press and threw it in the river. Lindheimer retrieved it, and the paper went to press with the story the next day.

Lindheimer died in 1879. In 1936, the State of Texas placed historical markers at his home in New Braunfels and at the Comal County Cemetery, where he is buried. The New Braunfels Conservation Society and New Braunfels Master Naturalists lovingly preserved his home and garden, which are constructed in classic German fachwerk style. Today, gardeners, naturalists, and Texas history enthusiasts visit the home, which remains a quiet shrine to this philosopher and pioneer of Texas plants.

PRICKLY PEAR_PHOTO BY ALAN CRESSLER COURTESY OF LADY BIRD JOHNSON WILDFLOWER CENTER

INDIAN PAINTBRUSH - CREDIT W.D. BRANSFORD COURTESY OF LADY BIRD JOHNSON WILDFLOWER CENTER

Comment

Comments